Over twenty-five years pass before Derbyshire is approached by Peter Kember (Sonic Boom) and begins to create music once more just prior to her death in 2001. It’s a narrative that has been replicated again and again – in journalism, in academia, in dramatisations of Derbyshire’s life as well as the fan cultures devoted to her.

In the laziest and most reductive versions of that basic narrative there’s a reliance on the well-worn tale of the tragic self-destructive artist with the added appeal of celebrity gossip and speculation as Derbyshire’s post-BBC life is often summarised as a decline into alcoholism until a last creative gasp thanks to the revivifying presence of Peter Kember.

A 2008 piece about Derbyshire in The Times is a textbook example of this tendency with the item dwelling more on claims about her ‘chaotic love life’ and collaborations with McCartney and Jimi Hendrix. There’s a strange emphasis here on the projects that Derbyshire might have done (the electronic backing to ‘Yesterday’) or did not take place (the tantalising however erroneous Hendrix suggestion), partnerships with famous ‘great men’ rather than the significant work that she did create.

That work included her collaboration with the dramatist Barry Bermange on the four ‘Inventions for Radio’ (1964-5), which resulted in a new genre of radio feature whose audible influence can be traced to figures as diverse as Pink Floyd and Jonathan Harvey, and her partnership with the artists Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield, all of which represented some of the projects that she was most proud of.

It’s difficult to dispel some of the most deep-rooted of these myths but we’re now able to tell a more complex and nuanced story of Delia Derbyshire’s life. If the core facts (and fiction) feel so familiar that might be in part because, by comparison, we have known so little about the other phases of her life, especially her origins and post-BBC work.

How did somebody from a working class background in Coventry, growing up in Britain in the 1940s and 1950s develop an interest in electronic music when it was not being taught in schools (or higher education for that matter) and opportunities to hear it were extremely limited? And what did she do after she left the BBC? Did she, as Louis Niebur states in his book Special Sound: The Creation and Legacy of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop (2010), retire completely from music by the mid-1970s? For many years, the widely held assumption was that she did. Yet, far from disappearing from view in 1973 and withdrawing completely from creative activity, as has often been reported, Derbyshire was still active as a practitioner into the 1980s, albeit in a far more ad hoc manner and her public output reduced to the point where it appeared to many that she had ceased to create.

Much of that counter-narrative has emerged as a result of research generated by the Delia Derbyshire Archive, housed at the University of Manchester’s John Rylands Library. The Delia Derbyshire Archive has grown considerably since it was first acquired in 2007 and now includes donations from Derbyshire’s friends and colleagues as well as a substantial collection of material from Derbyshire’s childhood, including some of her first writing about sound and music in which we can see her creative personality emerge and develop.

Her schoolwork demonstrates her growing affinity for sound and interest in the sonic potential of everyday objects. In one story she imagines a dusty music shop where the instruments and other items, a music stand and metronome, come to life at night, dance and play hide and seek with particular emphasis on the sounds each item makes as the dust sets them off sneezing and the double bass bursts out laughing (“You did not know a double bass could laugh? Then listen carefully when you next hear an orchestra; you might hear the ‘POM, POM, HA, HA, POM, POM, HO, HO,’ of Little Willie, the double bass”). Elsewhere she writes frequently about her burgeoning love of music (“my favourite hobby”) with particular mentions for Bach, Heller, Mozart, Haydn, Purcell, dances by Shostakovich and, above all, Beethoven’s sonatas (with the twelve-year old Delia describing them as “the pieces I like best… because they are so interesting”).

There are also numerous examples of Derbyshire’s love of visual art, which would become a driving concern in her work both within and beyond the BBC, taking in projects about Goya, Henry Moore, Paolozzi and Picasso as well as a series of fruitful collaborations with Hornsey College’s Light/Sound Workshop which resulted in several pioneering events that experimented with the relationship between electronic music and visual projections. Derbyshire’s schoolbooks are full of visual miniatures and doodles – often intricate, abstract shapes and geometric formations that are essentially looped and it’s here that we can perhaps see the origins of her later interest in loop-based music and the process of repeating a musical structure or sonic element and gradually augmenting its form.

Delia’s childhood drawings and visual loops

Delia’s childhood drawings and visual loops

The core of the Derbyshire Archive, however, is made up of items that she had kept with her after she left the BBC: paper documents and correspondence relating to many of her freelance and some of her BBC projects, including scores (often using conventional notation but also Derbyshire’s own graphics) and work-in-progress notes and 267 tapes, in varying formats but primarily 10.5” reels, which feature final mixes, draft edits and make-up tapes where one can hear certain projects in varying stages of development as well as recordings of non-Derbyshire material.

Delia’s graphic notation

Delia’s graphic notation

These tapes are revealing of Derbyshire’s own diverse tastes and interests in music: Mozart, Penderecki, Stockhausen, Can, Ray Davies, Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers and Yusef Lateef’s 1961 Eastern Sounds album. What also becomes clear from the freelance tapes is Derbyshire’s resourcefulness in recycling, repurposing or reinventing existing material from her own back catalogue, sometimes transforming a favourite sound source (her beloved green metal lampshade) into a new configuration or lifting a cue directly from one production into another.

The recording of a boy chorister (John Hahessy, later Elwes) which provides the basis for the entire score of Amor Dei is recycled by Derbyshire for several later projects, including her sound design for Peter Hall’s 1967 Royal Shakespeare Company production of Macbeth. There is also clear evidence in the archive tapes of Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson, her close friend and colleague at the Radiophonic Workshop, sharing material from earlier productions on new freelance projects outside of their BBC commitments, whether for Unit Delta Plus or Kaleidophon, the two independent facilities they set up in the late 1960s with Peter Zinovieff and David Vorhaus respectively.

One of the best examples of Derbyshire and Hodgson sharing material can be heard in her work for ‘Poets in Prison’, a live event produced by Edward Lucie-Smith as part of the 1970 Festival of the City of London. The project sought to explore ‘one of the extreme situations which tend to produce poetry’ and featured semi-dramatised performances of poems written in prison. Derbyshire’s music for the event included new material but one poem was scored by a mix of earlier BBC projects: Derbyshire’s ‘atheism’ movement from her music for Amor Dei (1964) blended with Hodgson’s ‘Thal Wind’ from the first Doctor Who Dalek story, broadcast across late 1963 and early 1964.

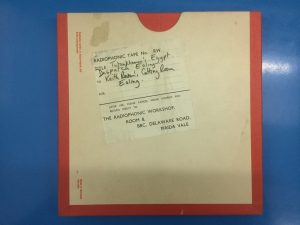

The vast majority of Derbyshire’s BBC projects, including the original Doctor Who tapes, are contained within the BBC Radiophonic Workshop Archive, housed in the BBC Archive Centre at Perivale but Derbyshire’s personal archive at the University of Manchester Library holds a number of key BBC works, including the first two Inventions for Radio from 1964, The Dreams and Amor Dei, a 1971 Schools Radio dramatisation of the story of Noah which finds Derbyshire creating a series of synthesiser-based dances with an infectious groove and wonderful evocations of the animal calls of different creatures on the Ark, and Tutankhamun’s Egypt (1972) one of her last major assignments at the BBC before her departure in 1973.

One of the tapes for Tutankhamun’s Egypt (1972)

One of the tapes for Tutankhamun’s Egypt (1972)

Tutankhamun’s Egypt was a problematic production and, according to Brian Hodgson, marked the real beginning of Derbyshire’s “disintegration” and disillusionment with, as she later put it, the “accountants” who she felt were taking over the running of the BBC. Derbyshire had mapped out her concept for this thirteen part factual series in advance, which included sampling a recording of the silver trumpet found in Tutankhamun’s tomb, but the original production schedule was changed late in the day and the transmission order of the episodes swapped so that Derbyshire was left working on re-scheduled episodes right down to the wire as they were being dubbed (her frustration is audible in some of her introductions to the respective cues).

For Hodgson, it was on this production “when she really started withdrawing from everything” as “the pressures of the deadlines were becoming more and more and she hated pressure.” Hodgson would try to help Derbyshire, inviting her to join him at his new independent facility, Electrophon, and collaborate on the score for the horror film The Legend of Hell House (1973). Although Derbyshire was credited on the film, her actual contribution to the production was, according to Hodgson, “confined to having dinner and standing around taking snuff.” Instead, the music was created primarily by Hodgson and an uncredited Dudley Simpson.

Derbyshire was not quite withdrawing from everything however. At the same time as her career at the BBC was coming to an end she was developing one of her most rewarding collaborations, with the visual artists and filmmakers Madelon Hooykaas and Elsa Stansfield, known collectively as Stansfield/Hooykaas.

Derbyshire first partnered with Stansfield on the sound for Anthony Roland’s award-winning art film Circle of Light (1972) and that was followed by two films with Stansfield/Hooykaas: One Of These Days (1973) and About Bridges (1975). Each film would see Derbyshire involved from an early stage in the production – a marked contrast with the eleventh hour nature of Tutankhamun’s Egypt – and it is perhaps not surprising that she would generate a substantial amount of new material rather than repurposing earlier sounds and cues with the score for the first film based primarily around manipulations of the human voice.

Although only collaborating directly on two films with Stansfield/Hooykaas, Derbyshire’s friendship with the two was enduring and she would influence their later experiments in video art: Labyrinth of Lines (1978) sampled Derbyshire’s score for One Of These Days but Stansfield’s electronic sound for works such as Running Time (1979) displays a strong Delian influence with ambiences and looped rhythmic sequences created from everyday sound sources.

It was Stansfield and Hooykaas who introduced Derbyshire to the Polish-born artist Elisabeth Kozmian in the late 1970s. By now, Derbyshire had returned to London after living and working for several years in northeast Cumbria by Hadrian’s Wall, first in the village of Gilsland and then at the remarkable LYC Museum and Gallery, where Derbyshire was an assistant to the Chinese-born artist Li Yuan-chia.

The site of the LYC Museum and Gallery at Banks in Cumbria

The site of the LYC Museum and Gallery at Banks in Cumbria

Derbyshire was not without music during these years and had with her two pianos, a VCS3 synthesiser and a much-loved spinet. Back in London she composed a solo piano score for Kozmian’s “experimental documentary” Two Houses (1980) and followed that with a demo cue, augmenting electronically Kozmian singing a Polish folk song, for an unmade film. These projects see Derbyshire still active as a composer and musician seven years after it has often been reported and assumed that she had retreated from creating new music.

According to Clive Blackburn, Derbyshire’s partner after she left Cumbria until her death in 2001, Derbyshire would take on the occasional project and made several visits in the 1980s to Adrian Wagner’s studio where she worked on new music, including the title theme for a programme about Stonehenge.

It’s all too easy to sweep over this lengthy phase of Derbyshire’s life and see it as an inexorable fall into decline and defeat but to do so would be to deny Derbyshire any agency in making principled decisions about what projects and roles she wanted to take on. None of this is to pretend that Derbyshire’s post-BBC life was free from difficulties but neither was it without music and creative activity, whether that was running an art gallery, composing for piano or playing the spinet for her own delight. Just as her music defies easy categorisation, her life also resists neat summaries and clichéd narratives. We still have much to learn about her work and methods and some mysteries may never be resolved but that is perhaps something to celebrate and will ensure that Delia Derbyshire continues to surprise and enthral.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Mark Ayres, Clive Blackburn, Brian Hodgson, Madelon Hooykaas, Elisabeth Kozmian, Mark Roland and Andi Wolf for their invaluable help with researching and writing this article.

PLEASE CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO DD DAY 2018 FULL CONTENT PAGE