An interview with David Vorhaus about producing the “An Electric Storm” album in 1969 with Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson

DD Day instigator and project manager, Caro C, met up with David Vorhaus to enquire more about “An Electric Storm” by White Noise. White Noise was a band that came from Kaleidophon studios made up of David, Delia Derbyshire and Brian Hodgson (Delia’s friend, fellow BBC Radiophonic Workshop team member and collaborator on projects like “The Legend of Hell House” soundtrack in 1973).

Apparently “An Electric Storm” didn’t sell well when it was released but David Vorhaus talks of the album outselling lots of number ones as one of the longest selling records. It was no.1 in the Netherlands for a year apparently, where there are cafés dedicated to the album. It is a much loved and influential album for so many artists and music lovers. So it just goes to show, you cannot predict the impact of your work. Caro was curious to ask David more about the production of this album and how it came about.

CC: I understand you made “An Electric Storm” without synthesisers – this does blow my mind a little. Did you not have a VCS3 at this point?

DV: It wasn’t invented yet. It (the VCS3) came with a crate of champagne which probably cost more than the synthesizer! We got it not long after we finished, but the album was all done by tape manipulation.

CC: I spotted in the archive there was a note that you wanted the album cover to glow in the dark. What happened with that idea?

DV: Thank you, I think it was a brilliant idea too! And it was also a very commercial idea in that obviously it would be great to have our record in the shop windows and record shops want people to look in their windows. And when they turn the lights off, if there’s something glowing in the dark, it pretty much guarantees our album would be in the shop window. But it cost a whole penny extra and the record company just said no. We have the original prototype cover and that does glow in the dark. This [White Noise] T-shirt glows too but not for long – we can’t put uranium in them anymore.

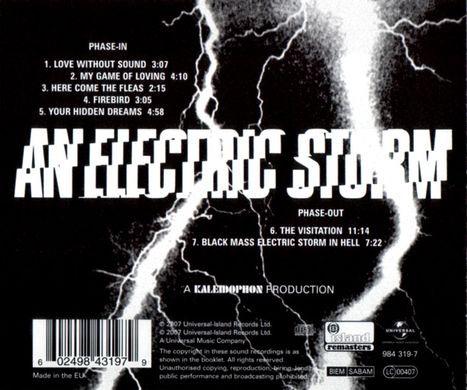

CC: I love the extra angles of creativity in the album. For example, “phase in” and “phase out” instead of side 1 and side 2. Where did that idea come from?

DV: We thought those up as it wasn’t a simple one side or the other side, but the two sides are quite different. Chris Blackwell suggested we be more experimental but I thought it more sensible to have a side with more pop-py tunes that people can sing and the other side would be really weird stuff. Then the first side could hopefully get radio play and Kenny Everett must have played those sound effects a thousand times. And of course the other side wasn’t going to get any radio play, we knew that, but people do love it. I can’t believe that people like that “electric storm in hell”.

Another stroke of luck is that Chris Blackwell was brilliant. He really started this whole thing. When I went to see him he said make it weird. But I said no, no, I want a hit single. He explained that the average buyer of singles was under 13 years old; singles don’t make much money, they were only to advertise the album. We worked out how much a hit single made which was about £3000 – about £60,000 in today’s money. So he wrote out a cheque for £3000 and said “right you’ve had your hit single, now go and make the record you want to.” Now that was an offer I couldn’t refuse!

CC: How did you meet Chris Blackwell?

DV: Brian organised that. He knew a theatre agent who knew Chris, so he connected us. But Chris wasn’t around when the album came out and the rest of them were a complete waste of time. They didn’t even listen to it. They said there was no advertising budget because it wasn’t a commercial record. During the creating process there was no help or support, not a word, you’d think there would have at least been a phone call. A year later we received a letter saying if we don’t receive the record within seven days, our solicitors will be taking action to recover the advance. Very nice. Charming. We did it in a night. It had taken a whole year of hard work to do the three quarters of it and we basically did the rest live, pausing and playing. I think if we had done the whole album like that, it would have disappeared but people went for one track like that, because there wasn’t really anything else like that.

CC: One of my questions was, who was the drummer and where did you record them?

DV: Paul Lytton was the drummer. He was a dentist by profession and a very good jazz drummer. We built a studio on Camden High Street, Kaleidophon. We built it out of a derelict building.

CC: Who built it?

DV: We did. Brian, Delia and me. And John Whitman – the guy who was singing. He was my best friend at school. We literally built the place. When we got the deal with Chris Blackwell, we had a year to make the album and they didn’t know that we didn’t even have a studio. So we had to get the place, build the studio, build the gear and then record the album.

CC: How did you get your microphones? And how did you record the drums, can you remember?

DV: Basically, whenever we got a job, like we did some work with the ballet Rambert, the fee was the cost of what we needed. We had two or three mics for the drums. And we recorded all the vocals in the studio.

CC: How did you find the vocalists? Was it people you knew?

DV: There was a bit of luck involved with the vocals. John Whitman, my friend from school sang the male voice part. But he had a low bassy voice. We decided the first number we did which was “Love without Sound” was too slow and should be a bit faster so we sped the whole thing up which meant of course pitching the voice up automatically. You couldn’t do one without the other in those days. So he became kind of androgynous even though it was a very low bass voice.

CC: Fantastic, I didn’t know that!

DV: It’s almost fluke that it worked. But the other voices were just people I found on the street, literally. Things like “My game of loving”, that really was my game of loving! There were only two lines for the whole song so I repeated them in different languages. And I found people I picked up, and would bring them into the studio. I wanted to say the words in Swedish, German, French, and these were people I just met who said the words in whatever language. A lot of the voices were done by a singer Island supplied but she wasn’t that great. John Peel said he loved the album except for the vocals. He said he had to put his fingers in his ears when the vocals came in.

CC: Who wrote the lyrics for Firebird?

DV: Firebird and Love Without Sound, we wrote that.

CC: I hoped that was the case.

DV: It wasn’t John MacDonald (who wrote much of the album’s lyrics). Actually come to think of it, I wrote most of that. One of the stories I was thinking of telling you about was when we went skiing. I was kind of showing Delia how to ski – I used to instruct and could stand on my skis and lean forward until I could touch my nose on the snow.

CC: Strong core!

DV: It’s more the hamstrings. It had been a year since I’d been skiing so I wasn’t so fit. I was pulling back up and a couple of springs went in the back of my hamstrings and I was crippled. I remember sitting there for a day or so and thought of the last lines of Firebird which were “Just as high on a rut looking up as I was in a cloud looking down.”

CC: Is it about Delia?

DV: It was with Delia. It was appropriate. Edgar Froese (electronic music pioneer of Tangerine Dream) loved that. I went to see him at a gig and he said he carries his favourite 12 tracks around his neck, and Firebird is one of them.

CC: I’ve heard a lot about the revolutionary stereo effects you used on the album. Can you tell me more about what you were up to?

DV: Well that was kind of the motivation to make an album as the electric storm concept needed to be in stereo, not mono. So basically I did everything I could think of. Obviously phasing, where the technology of phasing was literally a flanger using tape. But other things like moving stuff around, speakers and relays and switches. The last track on the phase in – “take my hand and you’ll begin to understand” – written by John MacDonald. I thought that was quite an apt topic. It’s basically about being gay and it was hidden. In those days it was still criminal, you could go to prison.

By then I was getting quite fluent with using the technology we’d made. The sounds are jumping around by relays – I had a power amplifier running a DC waveform and jumping it around. And these relays were literally smoking, you could smell the ozone in the room because they were sparking. It was all done with hardware, hard hardware not the invisible switches you have inside [now]. When I made the first sampler it had a sample time of 45 minutes. The first samplers had less than a second. And it was tape quality because it was a tape. The motor of the tape recorder was driven essentially from an oscillator and the oscillator was controlled by a keyboard. So you could set a frequency of say, 50 Hertz which you could set on middle C. Then as you went up or down the steps, the frequency of the oscillation would go up by that amount. Now you put that frequency into a 100 Watt power amplifier, a valve thing, and it then goes from there into a mains transformer backwards, so it comes out at 240 Volts and that goes into the Capsten drive of a tape recorder. So the mains frequency is effectively controlled which controls the tape recorder.

CC: That’s having the electronics knowledge.

DV: It’s thinking and putting a few ideas together. It’s very simple but I don’t know why it hadn’t been done. I can think of one think of one problem: it takes a while to get there, it doesn’t instantly get there. There’s kind of a delay, it wows up to the thing. So if you want gliding sounds it’s perfect. Otherwise what I did was use an envelope effectively to cut out the glide. So there was a delay time but the note didn’t come in until it had stabilised at the particular pitch. I’m not claiming it was the first sampler, but it was a first sampler.

So many other things… There was one thing that wasn’t my idea. It was the BBC’s mistake which was quite interesting. They wanted a device to be able to broadcast and talk to crowds without that feedback that happens, howlround. So they thought, if they could make a device that could shift the frequency of a sound it will then come out at a slightly different frequency to the sound that went in and it won’t howl round. They spent years on this, many engineers worked on this and it probably cost millions in today’s money. When they first tried it out at some big event, they not only got howl round but the howl would come out at a different frequency then in again at another frequency so it went up and up and up or down and down and down so it was far more noticeable than it was in the first place! So they dumped this thing on the Radiophonic [Workshop) saying it’s a piece of garbage as far as they were concerned, maybe you can find something useful to do with it. Now we put this in a feedback loop, on tape feedback delay going back into itself and used this deliberately. And the opening of “Love Without Sound” was going through this thing [sings Sound, pitch shifting/bending) so the sound itself was being shifted up and up and would add to itself so you got all the micro tonal intervals repeated and added to the original. So you got this beautiful ethereal sound which of course nobody had ever heard. This was something, when people heard this, they thought what the f**k is going on here?

CC: Could you do basic panning stuff?

DV: Panning was easy. We didn’t have pan pots but we had a fader that would go this way and that way.

CC: Like a crossfade?

DV: Exactly, we call them crossfades now. You have 2 outputs. It’s about wiring things, playing around.

CC: Multi-dimensional comes up a lot in the description of the album.

DV: Martyn Ware (of Heaven 17, we see him quite a bit and he’s really helpful) is doing something with Bowes and Wilkinson, they’re doing a proper three dimensional thing. Stereo is actually only 1 dimension. Surround sound is 2 dimensions. But you need it to go up and down (height) to get the 3 dimensions so you need speakers on your ceiling. My studio is proper 3D – two speakers on the ceiling and four around. It’s quite easy to do now. An ordinary 5.1 will cover it but you mount them differently, so they’re on the ceiling as well.

I was just thinking, what is really useful back then and still now is a bit of understanding of the basic technology, the physics. That knowledge is worth having. A kind of general knowledge of how things work, electrical things particularly. You don’t have to get back to basics and wire everything up but you can get boxes that do various things, connect them in ways you wouldn’t normally think of and it does give you the idea of “why not do this?”

CC: Did you have any glorious accidents? Things going up in flames?

DV: Yes, quite a few accidents. But accidents are part of what makes it work.

CC: At SynthFest UK last year (2018), you described Delia as your teacher…

DV: I knew physics and I knew music but nobody had put them together except in fantasy. And Delia was really doing this. I met her just by fluke. I was going to a morning college orchestra session, I was playing double bass and the conductor of the orchestra knew I was doing electronic music and he told me there was this lecture in the next door hall and of course I shot along to it. It was Unit Delta Plus (Delia, Brian Hodgson and Peter Zinovieff) and I was just fascinated and got talking to them. Within a week we had started Kaleidophon.

CC: And tape manipulation and that side of it – was she your teacher in that sense or did you know about that already?

DV: No. I didn’t know any of that. Tape manipulation was completely new to me. All the stuff you could do, the splicing and things, Delia has this down to a fine art. She’d chop stuff up really fast. And being able to find the right place, moving the spools. It looks fairly simple but it’s a physical art. People see you doing it but they often don’t understand what’s going on. You’re actually moving a sound across a tape head and you can tell by getting really close, to the point that’s on the head, you know the beginning of the sound, it’s right there. It took 2 or 3 weeks to learn that. Today it is a different way of doing things. But then it was completely new. You know, editing tape?! What, you can exclude sounds, you can pitch shift sounds, you can move around this, that and the other? I had no idea how that kind of stuff happened. It was a whole new vocabulary. And what the possibilities are in making music. It just became obvious. Think about it, if you know how to do this with tape so you can move anything anywhere – change the pitch, glide from here to there and all of these things. Literally, using a razor blade.

CC: A whole new language.

DV: Exactly, in fact it’s like language. If someone teaches you how to read and write it’s just unbelievable what you can do. You can invent stories, they don’t even have to be true, they can be fantasy.

CC: Finally I wanted to ask you about Brian’s input, he seems to play it down…

DV: He was definitely a proper partner in Kaleidophon. He was well worth his third, his share. He wasn’t a musician. He was very versatile with sound effects, with technology. We were doing stuff for National Theatre, Old Vic and that was very much his department. He was doing sound scores. For instance, the first Hamlet they put on at the Roundhouse with Tony Richardson directing. That was Brian’s department and he knew his stuff. He made the score to that which was not tunes…

CC: Sound design?

DV: Yes, what we would call sound design nowadays.

CC: And in terms of correspondence, there’s a letter in the archive where he talks about the album coming out. Nice silver font on the letterhead by the way!

DV: Oh, you saw the original one? On that onion skin paper?

CC: Yes, I think so.

DV: He did some admin but he also had the contacts. He got the Chris Blackwell deal by knowing someone who knew Chris Blackwell. But he wasn’t just admin. He was also definitely hands on when it came to, as you say, sound design. You can hear his stuff on some of the sound effects albums they put out. In fact, as soon as we got the deal with Chris Blackwell, before we even did the album, we were talking to someone and he said you’re coming up with these great sounds, how about doing a library record for sound effects? I said but it’s just sound effects, no one wants just sound effects, surely, there’s no tunes to them or anything. And he said, well you’d be surprised you know, radio shows use these, TV, film, they want sound effects of sounds that people have never heard before. There’s quite a field for that. And of course he was absolutely right. It was me being shortsighted saying how on earth would you want an album like that? He said, look, I’ll give you money, pay you to do this stuff. It was very successful. It was perhaps the first electronic library album. And Brian was half of that. Delia was the other half. I only did 2 pieces as I’d done so little at that point, this was right at the beginning.

CC: Wow, that’s ace. And are you proud of “An Electric Storm”?

DV: Yes. I am, looking back on it. And you help a lot. Saying here it is, 50 years ago and we’re still interested. It keeps the depression away [laughs]. It’s nice that people are still interested.

CC: It’s honouring it really. I think at the time when you know you’re doing something that isn’t going to be a hit single, but it’s your passion, it feels right, you are following your creative trajectory…

DV: It’s exactly that. What’s the best result you can get.

CC: And what feels right for you.

DV: Yes.

——————————————————————————————

David Vorhaus will be speaking at DD Day 2019 MCR at Spirit Studios (23 November), DD Day 2019 LDN edition at British Library (30 November) and Inner City Electronic 2020 (Leeds, UK, date TBC).

Brian Hodgson will contribute to the mini-symposium at DD Day 2019 LDN edition at British Library (30 November).